“ Do good, say good and think good. ”

– Ahura Mazda

The Persian poet and author Ferdowsi (940 – 1020) renown with his masterpiece Shahnameh – The Book of Kings, illuminates the ancient history of Persia dating back to 1500 BC. He recites the myth of creation, the personas of ancient kings and heroes, and the combat of the good against the evil through the march of history. The stories take stage in the backdrop of Zoroaster, who is said to be the Persian prophet known with his sacred book, Avesta and having founded the monotheist religion in ancient Persia. The essence of Zoroastrian teaching “ Do good, say good, and think good ” constitute the kernel of Shahnameh. It is woven in the stories of heroic battles against all forms of evil, in which bravery is driven by an unwavering faith in God., and the righteousness of the hero changes the course of events. Illustrated by the eminent miniature painters of the epoch, it also stands as a treasure of Persian art. The mystical spiritual tradition putting forth the lessons of the saints and sages attributes a magical hue to the book.

It is believed that the celebration of Nowruz, the Persian New Year on March 20 dates back to the times of Zoroaster (~1000 BC) and it is sublimely recited in the story of king Zahhak, who is a destructive evil personality, and young Fereydun who is the embodiment of righteousness and the good. Ahriman, who represents evil in Zoroastrian belief, tells Zahhak that it is his right to ascend the throne by killing his father. As Ahriman mutters in his ear, he places a snake on each shoulder.

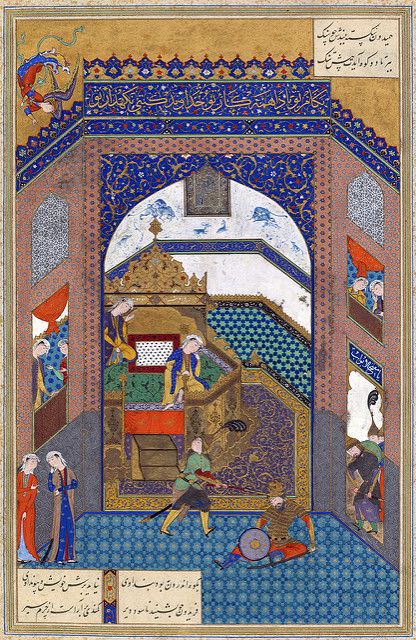

In turn, Zahhak kills his father as plotted and ascends the throne. The new king gradually turns into a cruel tyrant. His rule knows no mercy. The two snakes placed on his shoulders are never to be satisfied. Ahriman, who kept watching his progression, comes up with a new idea and warns Zahhak that his brain will get sick if he does not feed the snakes with the brain of the youth. Thereupon, the king wastes no time to set off the massacre. The young people of the country are snatched one by one, and then in pairs brought in the dungeon of the palace waiting to be killed. The people helplessly drifted in desperation and fear. The youth population was steadily decreasing; they either fled if they could or were killed. The despair that reigned was so great that even spring was overdue. No green shoots, no buds were showing up. Restraint surrendered all, humans and nature alike.

Kâveh, a blacksmith already lost three sons, was contemplating in his affliction that he could no longer endure this. But his last remaining son revolted and decided to join up with his friends to make iron weapons in secrecy. They began collecting the prepared weapons in the village of Fereydun, a brave, good-hearted and luminous young man who living with his mother. When the group of friends asked Fereydun to be their leader, he agreed. They soon began to devise a plan to save the people from the insatiable king.

Heaving heard about the upcoming rebellion through his network, the king summoned the blacksmith Kâveh with the intention of making an agreement with him to suppress the foreseen rebellion. He proposed the deal : In exchange for sparing the life of his last remaining son, the king demanded the blacksmith’s partnership to the suppress rebellion. The blacksmith after having refused all the offerings of the king, put his iron mace on his shoulder and left the king’s court. On his return, he gave his special mace to Fereydun to fight for the people.

The young people communicated to each other with fires they lit on the hilltops. They gathered their iron weapons and marched off towards the palace on the 20th day of March.

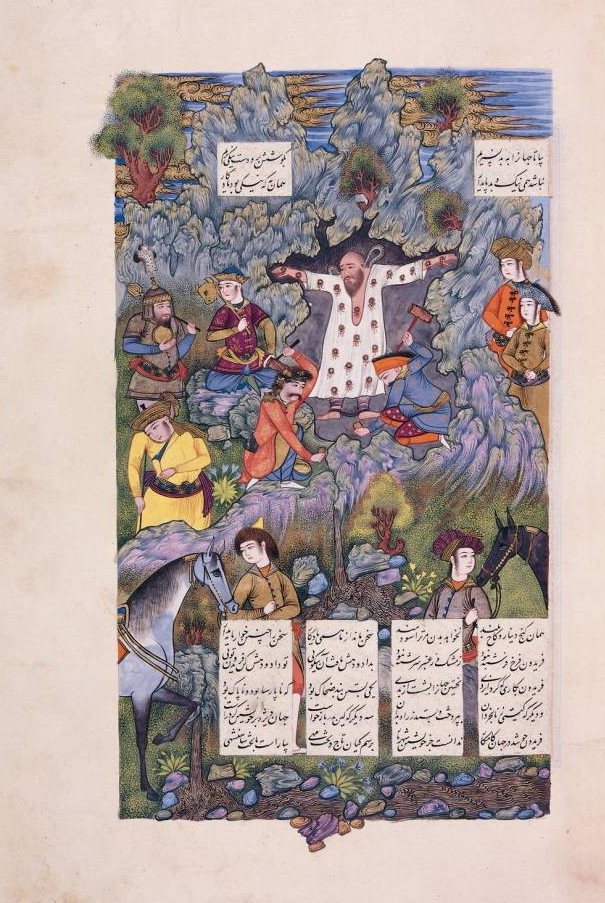

Fereydun got hold of the king and was about to strike his head with his mace, but Ahura Mazda, the representative of goodness ordered not to kill stating that “ Zahhak’s time to die has not yet come ”. Fereydun obeyed the command.

They took Zahhak to Mount Damavend, the high and mighty mountain revered in the region, placed and tied him up in a cave. Ultimately he did not die. The story has it that as long as humankind exists, Zahhak will remain there until the end of the time.

After the victory of the young people, spring arrived in the country. The trees turned verdure green once again, flowers sprung and the earth took on its joyful colors.

Open fires were kindled, feast tables were set to celebrate the spring of freedom. Sweet melodies were reviving the spirits. The afflicting darkness that loomed over the country is finally lifted with the uprising flames of fire. Thanks to the brave efforts of the youth, the faith of Fereydun and the solid integrity of Kâveh, the country was saved.

Celebrating Nowruz in today’s Iran, is a deeply rooted tradition since the time of Zoroaster. It is the time for revival of the body and soul with renewing joys and passing over to new beginnings. On the countdown of Nowruz, the tables are decorated with wheatgrass, hyacinth flower, mirror, vinegar… invoking abundance, health, purification, and good omens for the new year.

Wishing you a healthy, bright and hearty spring…

Duygu Bruce