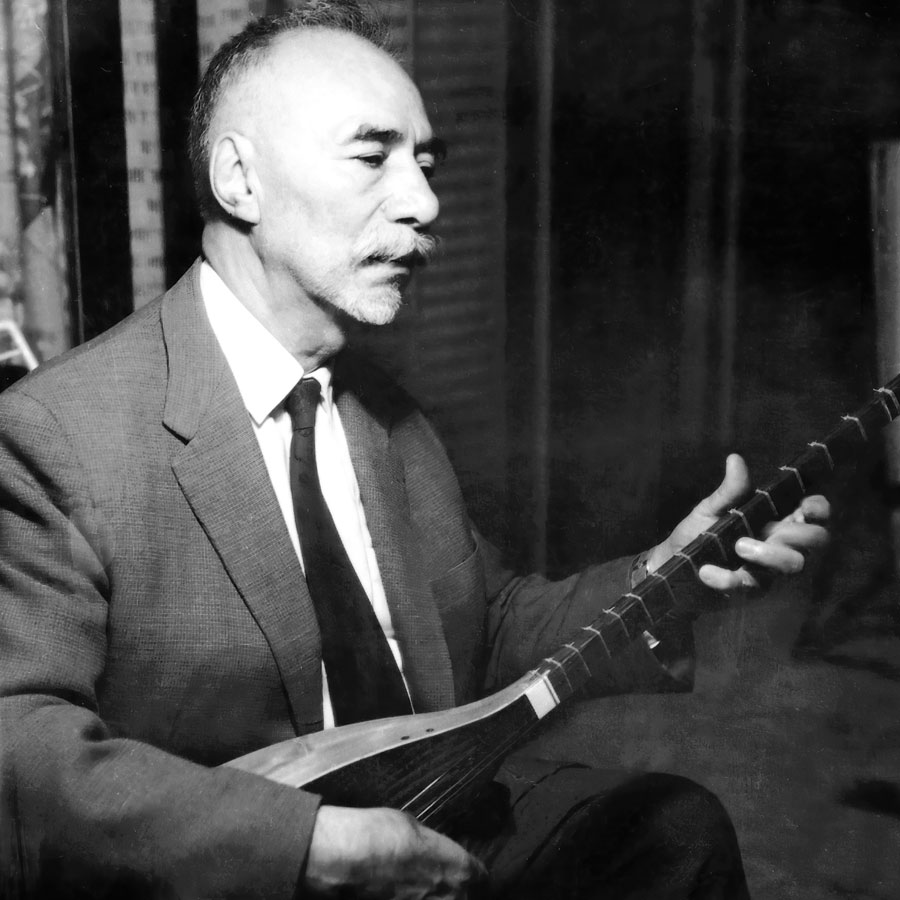

A master musician, an influential thinker and jurist, Ostad Elahi ( 11 September 1895 – 19 October 1974) said :

“Music has countless properties, most of which have yet to be discovered.”

Born in a small remote village in Iran, he grew up in a spiritual milieu where mystical traditions reigned everyday life. He was devoted to music very early on in his quest for meaning, self-knowledge, and transcendence. By the age of nine he was recognized as “ a peerless master of the tanbur ”, yet he only played it for himself. Occasionally, his relatives and visitors would come to listen to him. He neither gave a concert nor recorded his works professionally, and he made no attempts to teach. After staying as a hidden treasure for years and avoiding fame, his music would be known 40 years after his departure, when the instruments he played were displayed in a groundbreaking exhibition – The Sacred Lute: The Art of Ostad Elahi, at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2014-2015. A record-breaking number of visitors from all over the world got to know him and his music through this exhibition.

“ Ostad Elahi’s childhood was permeated with music, ” wrote Jean During in his book The Spirit of Sounds, dedicated to the Music of Ostad Elahi. He wrote :

Ostad Elahi was participating in familial gatherings where the instruments accompanied the songs. He was able to memorize an air by hearing it just once. As they had many visitors – most of them tanbur players – from neighboring regions, Ostad Elahi was able to experiment with different styles and playing techniques from Iranian and Iraqi Kurdistan, Azerbaijan and Turkey.” At the time when he went to take lessons from one of the master musicians of the period, Darvish Khân, listened to his playing and said to him with tears in his eyes, “ I have nothing to teach you ! ”

In addition to the ancient sacred repertoire of the tanbur, he also played the tar, Persian setar, Turkish saz, choghur, ney, violin, and the Kurdish tambourine – daf.

Ostad Elahi’s son, Dr. Chahrokh Elahi recounts :

In this profoundly spiritual milieu in which he grew up far from the noise and distractions of the world, the tanbur was his only companion and the confidant of his secrets. The quality of his spiritual education had made him advance in self-knowledge and knowledge of God. He had discovered the celestial world from which all Beauty originates. The sound of his tanbur was no longer that of two ordinary cords emanating from a wooden box – it was angelic melodies that fell from his fingertips and intoxicated the listeners. As a poet has said: So close to the melodies of the other world, are the moans of the tanbur: dry wood, dry cords, skin…Where does the sound come from ? The Beloved.

According to the witnesses, the movement of his hands was like a dance that carried the instrument away with it. The agent and the instrument, the subject and the object, were one, and the tanbur seemed to dance and sing by itself. As one witness writes : “…his whole attitude expressed peace, sweetness and majesty.”

He was one body with the instrument, in a relation so intimate that the tanbur became a living being, similar, in his own words, to a horse. Ostad Elahi said, “ the musician, like an experienced horseman, must exercise total control over his mount.”

On his extraordinary rapport with the tanbur one of his friends cited :

“When Ostad picked up his lute, you felt this extraordinary intimacy with it. In his hands, the instrument was a piece of wax to mold, an extension of himself. At the same time he showed the tanbur great respect and treated it as a sacred instrument.”

Dr. Chahrokh Elahi describes the supernatural power of his music as follows:

The fluid power and effect of his hand gave the tanbur such a strong resonance and sound that you had the impression that it was connected to an amplifier … sometimes his playing was so intense that you thought several instruments were playing together. This feature cannot be explained or technically reproduced under today’s known laws of acoustics.

He gives an example of the miraculous quality of his music invoking a memory:

The sound of my first tanbur was weak and no one wanted to play it. I told Ostad about this one day and asked for another. “Does it sound bad ? ” he asked and said, “ Show me ”. He took it and began to play: What a sound! You would think it was an orchestra… This instrument could never make such a sound again.

“ It is above all the mastery of sound,” experts said : “ Give him a dry piece of wood, and he will still be able to make the sounds of the tanbur from it.”

Yehudi Menuhin, master violinist and conductor, heard his music during his visit to Ostad Elahi and expressed it in the following words:

It was very sensitive, very powerful music, and at the same time very precise and pure. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, its refined power, exactly like some sort of laser.

Ostad Elahi has more than 300 pieces in his repertoire. He never played the same air the same way twice. “ Each new performance ” says his son C. Elahi “ eclipsed the last. It does not find its way according to a map; it blazes its own trail.”

Jean During marks :

What distinguishes Ostad from professional musicians is he was never conditioned by the need to please or to be heard by others. He played for himself alone or “ for God.” This is how his art transcended the music of his native community, and reached a level of universality, where listeners from every horizon found themselves touched in the deepest parts of their being.

Against tradition, his music develops in such a way that it touches the brain and the nerves more than the feelings and the heart. The subtle and profound effect of his music “awoke the soul,” stated one of his loved ones. Ostad himself said on one occasion that “ the vibrations are directly transmitted to the brain and could produce the appropriate effects in relation to the airs that were played.”

Ostad Elahi himself describes his music as follows:

These melodies are not ordinary, they are the music of the soul. It should not be used like any other music. If they are listened to with a spiritual intention, one will benefit from them.

In answer to Dariush Safvat a traditional master who asked him how to attain hâl – a state of grace in which, without material cause or artificial stimulant, the soul felt warmth and joy, a feeling of lightness and rapture, Ostad Elahi replied:

As long as you are thinking about the rules and techniques of music, you cannot achieve such a quality and reach that state. When you manage to no longer think and are concentrating on yourself, or, in other words, when you delve within yourself, then the veils will be lifted.

[…]

It is the music that must follow the inspiration of the musician, and not the musician that must follow the music.

According to Ostad Elahi, those who are susceptible to the arts, and to music in particular, enjoy a certain advantage in traveling the path. As several myths relate, one of the reasons for this is that music is considered to be a divine creation, a language of the soul. Thus an individual who is receptive to this art will, in theory, have easier access to the Source, and his progress will be somewhat easier.

“ This is one of the many reasons why he never played the tanbur outside of a spiritual intention and context, and why he never wanted to be mediatized. He did not want his music to run the risk of being turned away from its moral goal, ” reflects J. During.

“The tanbur speaks,” Ostad Elahi used to say, “Listen to it.”

There have been numerous cases witnessing the beneficial effect of Ostad’s music, J. During recounts that one of them is the Persian scholar and a Professor of mathematics who was stricken by a chronic depression which at times provoked suicidal thoughts. He disagreed with the dogmatic forms of religion in which he had been raised and had rejected outright spirituality and metaphysics. He would sometimes visit Ostad, and one day he came to his house in one of these moments of extreme affliction. He entered the room, where Ostad was in the company of several people, and he sat down without a word. Also without saying a word, Ostad picked up his tanbur. All the while Ostad played, the professor wept silently; when it was over he rose still without saying anything and left. His state was immediately improved and afterwards, he was able to reestablish his psychic equilibrium.

Famous choreographer and dancer Maurice Béjart heard about Ostad while he was at the Shiraz Art Festival in 1973 and visited him. Years later, he expressed the profound impact of this meeting on his life as follows:

He played music…and I cannot convey through words what I lived or experienced…this encounter induced a great change in my life, in my existence, and in my thought.

Ostad Elahi retired in 1957 after 27 years of public service and his home was always open to visitors. People from all walks of life came, among which were some artists and intellectuals from Europe would also visit him. Some were influenced by his teachings or were drawn to his music, and many saw a divine quality in Ostad Elahi’s personality. At these meetings, he adapted his discourse to the culture, religion and beliefs of the attendees, recites J. During and distinguishes the thought of Ostad Elahi : “ Spirituality, as Ostad thought, went far beyond culture and religious sects. Although rooted in a mystical tradition, his philosophy had a universal impact. The way his thought spread in the west also bears witness to this fact. ”

Ostad Elahi punctuated the significance of music for the soul :

If used with the right intention, music can connect us to the Divine, for music is related to the soul, and the soul is related to the Source.

You can watch here synopsis of the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York :

https://vimeo.com/127446525

You can listen below some excerpts from his music :

Shâh Khoshini Suite, Awakening, track 3 :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=piUL8pusuNA

Shekaste, The sacred Lute Vol 2, track 7 :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rywWVsxsCog

His youngest son and musical protégé, Dr. Chahrokh Elahi, plays several pieces from Ostad Elahi’s repertoire, including Saru Khani. Copyright © 2009 Nour Foundation. All Rights Reserved. You can listen below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AxCB923_QOY

Reference: All the citations in this post are taken from The Spirit of Sounds, written by Jean During