Peter Wohlleben, forester and the author of international bestseller The Hidden Life of Trees writes: “Our need of nature is an integral part of our humanity,” and “the bond that unites us with nature is never broken.”

He recounts how he discovered this bond hidden in him at a time when he was working to optimize the forestry output for the lumber industry, and trees were nothing more than profitable commodities for him. He recounts:

One day, as I was doing my daily job across the forest, I stumbled over an old tree stump.

When I examined the chunk of wood covering the ground in front of me, I saw different layers of moss an some unusual rocks attached. When I lifted the moss, I saw that that the trunk was still alive although it was 400 or 500 years old!

He marks this incident as the transformation of his relation with the forest and the change of his career to become a forester. He started to manage an environmentally friendly forest in Germany where he presently lives with his wife on a farmland cottage. He brought together what he gathered from decades of observation in the forests with the scientific discoveries in The Hidden Life of Trees. Here is a selection of facts about the intelligent life of trees :

- The underground fungi network around the roots of the trees is like a so-called wood wide web which expands over the years. It continuously sends electrical signals between the trees and serves as the forest internet and enable trees to communicate with one another in case of an attack, a change in climate, and for the nourishment of the saplings. It functions like the extended nervous system of humans.

- The root network is in charge of all chemical activity in the tree.

- Oak trees carry bitter tannins in their bark and leaves which make the taste bitter and kill attacking insects.

- Willows produce a specific acid to ward off insects.

- Mimosas, when touched, close their feathery leaves for protection.

- When trees are really thirsty, they begin to scream in the form of vibrations in the trunk, when the flow of water from the roots to the trunk is interrupted. The frequencies can be recorded by ultrasonic devices.

- The tree breaths through its needles, leaves and roots.

- The shape and depth of folds, wrinkles and cracks in the bark of the tree show its age.

- Also, the higher the green up the trunk, higher the age.

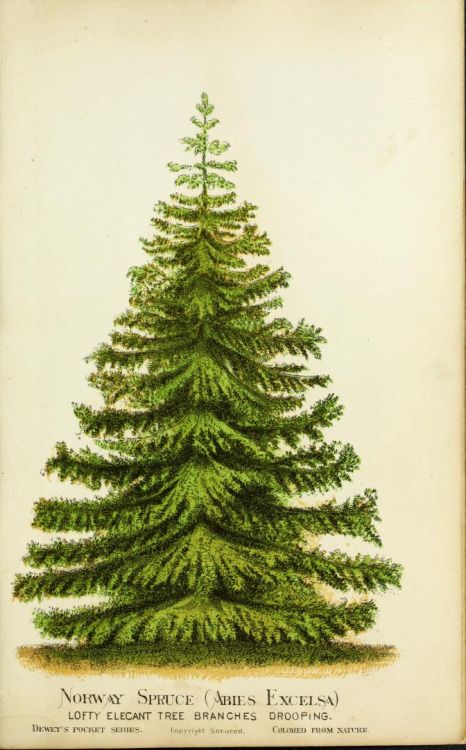

- The needles of the conifers remain on their branches for up to ten years.

- Oaks easily live more than 500 years.

- Because oakwood is permeated with tannins that keep away insects, wine matured in oak barrels taste better.

- Spruce, grown typically in northern Europe, and Siberia stores essential oils in the needles and bark which act like antifreeze in the winter.

- On a hot summer day, a deciduous forest is 10 degrees Celsius cooler than a conifer forest.

- It takes more than hundred years for true forest soil is to be regenerated. To make it happen, we need preserves of ancient forests free from any human interference.

- Diversity provides security for the survival of ancient forests.

- From the Siberian taiga to the rainforest, it is always the trees who transfer the essential life-giving moisture to inlands. Given the reciprocal relationship between trees, water and weather, forests play a crucial role in climate change.

He marks that the ancient forests which are essential for the earth are disappearing under the axe and the plow. But he warns that it takes 500 years for them to grow ancient forests once again unless if we take cautions today to preserve them.

He marks the resilience of nature despite the ecological harm done upon the earth. He proclaims that if we leave nature on its own even for a short while and suspend causing harm, it will revitalize and find ways to rejuvenate herself. Just like it rejuvenates us, he writes :

As we get in touch with nature more, our senses of touch, smell, hearing, and seeing are sharpened. We can recognize the smell of the mushrooms, of moss and pine; with a sharpened sight, we can distinguish the colors of the plants and animals more easily.

Perhaps it is the more primitive part of our brain which responds to the presence of the trees nearby for therein we find our biotope…

In our urban lives, the times are tightly controlled, punctuated. But the course of time is different in the forest. Having forgotten the watches and the cell phones, time resumes ample and available, one feels wider, free of constraints. When you return from the walk, you realize that a much longer time has passed than you thought.

[…]

In the forest, all slows down and subsides. The environment does not change every ten seconds.

The wind, the rustling leaves, hidden sounds, the rhythm of our steps… We start paying attention to the colors, the form of the trees, the scents. Nothing is like the urban hyperactivity. Our perception of time changes.

Now it is the time of the trees. Deep inside we find a rhythm which is all too natural to us. We reunite with our true part. That’s why we feel better and more joyful.

After all it is simply happiness to turn our gaze to a blue sky over the lush green of a forest and breath in the idyllic atmosphere. What a grace !

Duygu Bruce